Steve Jobs started Apple as a twenty-one-year-old with his best friend in his parents’ garage. Apple helped to launch the personal computer industry and became a billion-dollar company, but he made enemies out of almost everybody he encountered and eventually he was dramatically forced out. After leaving, he founded Pixar and began creating state-of-the-art animated films, whilst Apple started to decline and eventually began haemorrhaging money. A decade after being fired, he returned and took Apple from the brink of bankruptcy to the most valuable company in the world. He helped to launch personal computers, MP3 players, smart phones, and tablet computers, and completely revolutionised the computer industry, the film industry, and the music industry. He had such a massive impact on our world despite having zero technical expertise. Instead, he had incredible vision, taste, passion, charisma, energy, drive, and determination.

He was also deeply flawed. He felt abandoned by his biological parents who put him up for adoption when he was born. The rejection affected him profoundly and he grew up to be cold, self-centred, and confrontational. He tyrannised his staff, lashed out at his friends, and eventually abandoned a child of his own. However, his narcissism was also vital to his success. It made him incredibly ambitious and gave him the unshakeable self-confidence to endure setbacks, whilst his domineering leadership drove people to do things they didn’t think were possible.

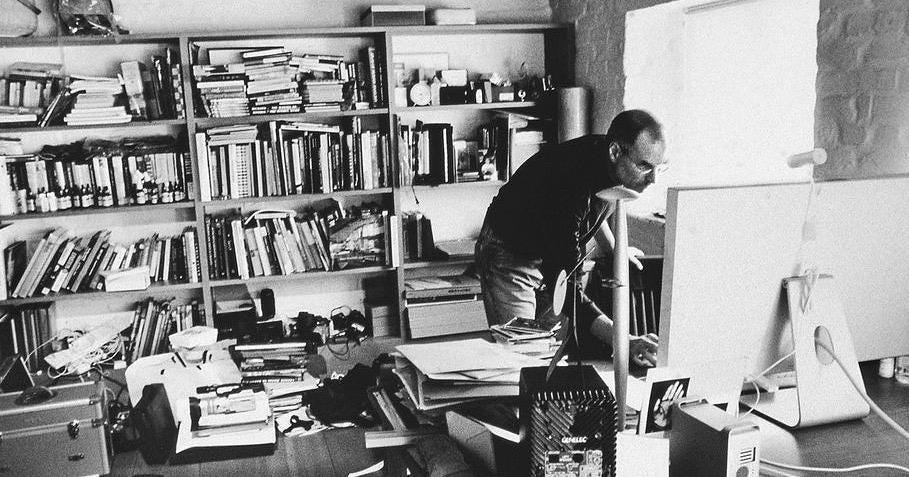

After he was diagnosed with cancer, he asked Walter Isaacson to write a biography of him. Isaacson interviewed him forty times as well as hundreds of other people who knew him at different times in his life.

I’ve summarised the biography as a series of notes.

The Life of Steve Jobs

Childhood

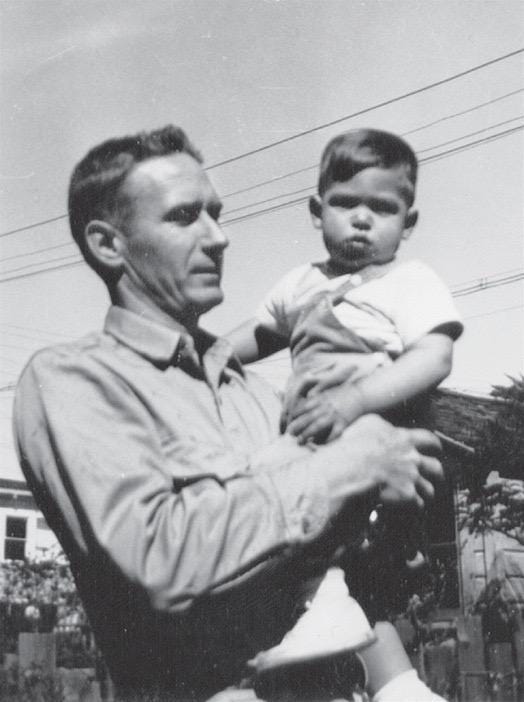

Steve Jobs was born on February 24th, 1955. His biological mother, Joanne, was from a strict Catholic family and his biological father, Abdulfattah, was a Syrian from a traditional Muslim family. They felt unable to marry because of the inevitable reactions of their families and Joanne’s Catholicism made her unwilling to have an abortion. So they put their son up for adoption and he was taken by Paul and Clara Jobs, who named him Steve. Two years later, they adopted a girl called Patty.

When he was six or seven, Jobs told a friend that he was adopted and she replied, ‘So does that mean your real parents didn’t want you?’ He ran home crying but his parents reassured him, ‘We specifically picked you out’, placing an emphasis on every word in the sentence. Jobs hated people referring to Paul and Clara as his ‘adoptive parents’ and always maintained they were his real parents.

Throughout his life, many of his closest friends believed that being abandoned by his biological parents had affected him deeply. A former girlfriend Chrisann Brennan said it left him ‘full of broken glass’ and other friends believed it had made him independent but also cruel and controlling. Jobs disagreed, ‘There’s some notion that because I was abandoned, I worked very hard so I could do well and make my parents wish they had me back, or some such nonsense, but that’s ridiculous. Knowing I was adopted may have made me feel more independent, but I have never felt abandoned. I’ve always felt special. My parents made me feel special.’

He was a bright child and his mother taught him to read before he started school. As a result, he was bored for the first few years there which made him rebellious and mischievous. At the end of fourth grade, he tested at a tenth-grade level. He skipped a year but he was bullied by the older children and eighteen months later he pressured his family to move house so he could go to a different school.

He became interested in electronics and when he was fourteen he looked up Bill Hewlett, co-founder of Hewlett-Packard, in the phone book and called him to ask for some parts for a project he was working on. Hewlett sent him the parts but also gave him a summer job working on the production line at HP. He later had a job at an electronics store and he went to electronic flea markets, haggled for parts and sold them to his manager for a profit. He once installed speakers throughout his home so he could listen to what was happening in other rooms from his bedroom until his father found out and made him remove them.

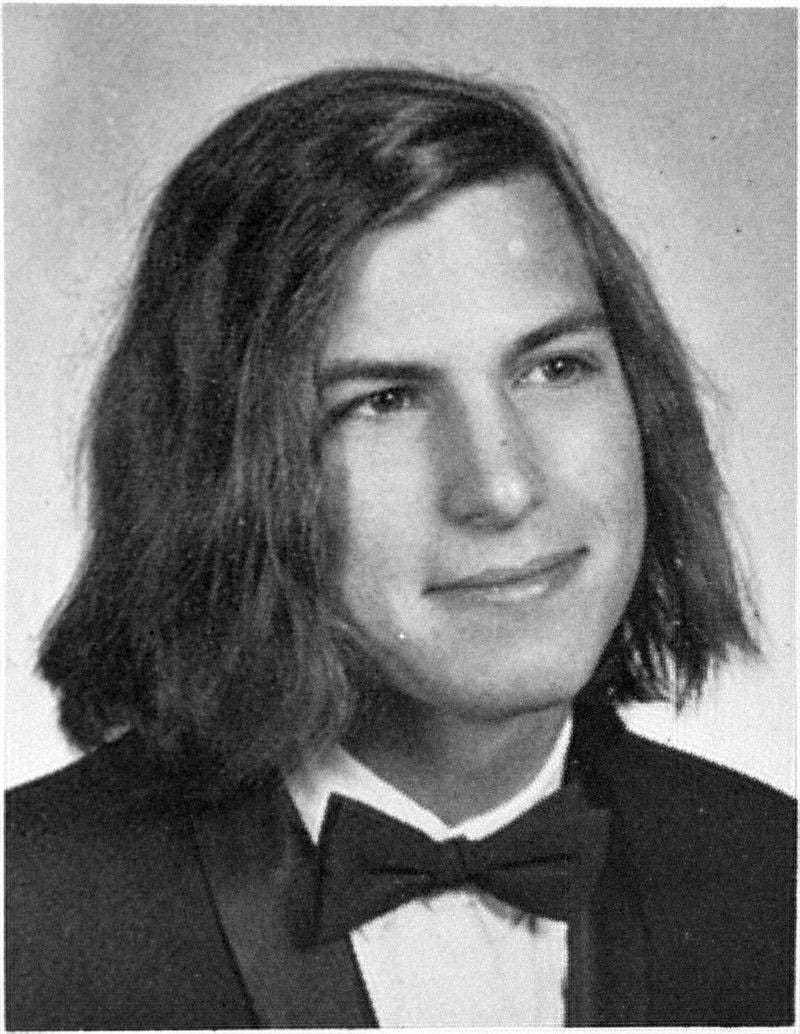

He grew up during the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s and embraced its focus on Eastern spirituality, music, and psychedelic drugs. As a thirteen-year-old he began his life-long study of Zen Buddhism and a couple of years later grew his hair long and started smoking marijuana.

During his last years at school, he started going on strange diets such as only eating apples or carrots for weeks at a time. He continued these ‘fruitarian’ diets for the rest of his life.

Steve Wozniak

When he was 16, he met Steve Wozniak. Wozniak was almost five years older than him and had the complete opposite temperament. Whereas Jobs was brash and wilful, Wozniak was shy, unambitious, and inscrutably honest. Wozniak was a prodigious engineer and as a seventeen-year-old he was redesigning the latest computers using half the number of components. Wozniak introduced Jobs to Bob Dylan, and together they collected bootlegged recordings of Dylan’s concerts. Dylan remained Jobs’s favourite musician for the rest of his life.

The Blue Boxes

In 1971, Wozniak read an article called ‘Secrets of the Little Blue Box’ about a hacker who had discovered how to make long-distance calls for free by using a toy whistle to replicate the tones that routed calls on the AT&T network. The complete set of the audio frequencies used by AT&T to route calls was listed in Bell System Technical Journal, and AT&T asked libraries to remove the copies they had. Wozniak and Jobs rushed to the library to withdraw a copy and then bought the parts to build a Blue Box to replicate the tones. When they had built it, they celebrated by calling The Vatican from a payphone pretending to be Henry Kissinger, ‘Ve are at de summit meeting in Moscow, and ve need to talk to de Pope.’

Jobs realised that they could sell the Blue Boxes, and they started building them. They cost $40 to make and they sold 100 for $150 each. This gave them the confidence that they could overcome technical problems and build functional products. They realised that the combination of Jobs’s vision and Wozniak’s engineering skills could be very effective. Wozniak would design the product and Jobs would make it user-friendly, market it and make a profit. Jobs later said, ‘If it hadn’t been for the Blue Boxes, there wouldn’t have been an Apple, I’m 100% sure of that.’

Chrisann

In his final year at school, he started going out with Chrisann Brennan and they spent their first summer together living in a cabin in the hills above Los Altos. They took LSD together and Jobs would play the guitar and write poetry whilst Chrisann painted. Jobs and Chrisann had an on-off relationship for the next six years and had a daughter, Lisa, together in 1978.

Reed College

After finishing school he went to Reed College, an expensive liberal arts university. At Reed he became close friends with Daniel Kottke and his girlfriend Elizabeth Holmes. Jobs and Kottke shared an interest in music, psychedelic drugs and Eastern spirituality. They became vegetarians, took LSD, read books on Zen Buddhism and built a meditation room in the crawl space above Holmes’s bedroom.

At Reed he became influenced by Buddhism’s emphasis on intuition. ‘I began to realise that an intuitive understanding and consciousness was more significant than abstract thinking and intellectual logical analysis.’

He also became friends with Robert Friedland at Reed. Friedland’s uncle owned an apple farm near Reed and Friedland turned it into a spiritual commune called ‘All One Farm’. Jobs lived there for a while with Kottke and Elizabeth Holmes until he realised Friedland was using the commune to make money.

After one term, he dropped out of Reed but persuaded the university to allow him to stay with friends in the dorms and attend the classes he wanted to. He took a calligraphy class and learned about different typefaces. ‘If I had never dropped in on that single course in college, the Mac would have never had multiple typefaces or proportionally spaced fonts. And since Windows just copied the Mac, it’s likely that no personal computer would have them.’

Atari & India

A year later, he decided to move back in with his parents and get a job. He saw a listing in the newspaper posted by the video game manufacturer Atari, so he turned up at their offices and announced he wasn’t leaving until they hired him. They considered calling the police, but chief engineer Al Alcorn saw something in him and took him on as a technician. However, his personal hygiene and arrogance quickly caused problems. He believed that his fruitarian diet prevented body odour, so he didn’t shower or wear deodorant, and he also regularly told people that they were ‘dumb shits’. Eventually, he was put on the nightshift so the other engineers didn’t have to work with him.

A few months later, he went on a spiritual pilgrimage to India with Daniel Kottke. In India, he became even more convinced of the value of intuition. ‘Intuition is a very powerful thing, more powerful than intellect, in my opinion. That’s had a big impact on my work…If you just sit and observe, you will see how restless your mind is. If you try to calm it, it only makes it worse, but over time it does calm, and when it does, there’s room to hear more subtle things – that’s when your intuition starts to blossom, and you start to see things more clearly and be in the present more…Zen has been a deep influence in my life ever since.’ After seven months in India, he came home and he returned to work at Atari.

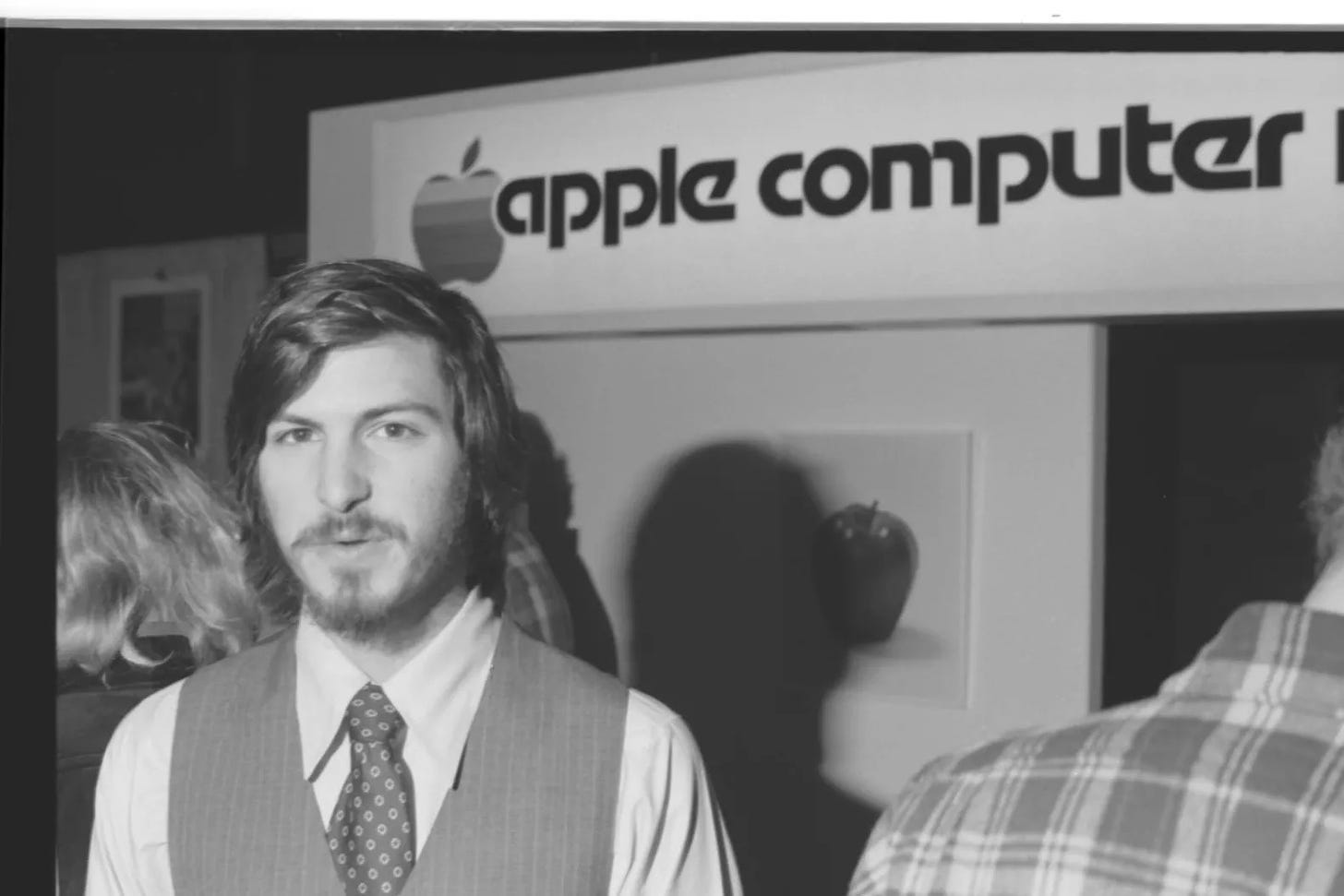

Shortly afterwards, Wozniak went to first meeting of the ‘Homebrew Computer Club’, a group of computer enthusiasts and hobbyists in Silicon Valley. At the meeting, he saw the specification sheet for a microprocessor – a chip that had an entire central processing unit on it. At the time, he had been working on a terminal with a keyboard and a monitor which could connect to a distant minicomputer. He realised that if he put a microprocessor inside the terminal he could create a single unit with a computer, screen, and keyboard – in other words, a personal computer. This would ultimately become the Apple I, and Wozniak worked on it in his free time after work and finished it three months later. Jobs was impressed and convinced Wozniak that they should sell them. Jobs sourced the parts and negotiated a deal with a co-worker at Atari to print 50 circuit boards for around $1,000, which they sold for $40 each. Wozniak sold his HP 65 calculator and Jobs sold his car and together they created a company in Jobs’s parents’ garage. Jobs was inspired by his time spent at Friedland’s apple farm commune as well as his all-apple diets and suggested the name ‘Apple’ for the company. They felt it made computing feel less technical and intimidating and it would place the company high in alphabetically ordered business listings, so it stuck.

Apple

He offered a friend from Atari, Ron Wayne, a 10% stake in the company to act as a tiebreaker if he and Wozniak disagreed. Wayne accepted and they signed a partnership agreement in 1976 but he quickly got cold feet. Eleven days after signing the partnership agreement, he withdrew. In return for his 10% stake, he was paid $800 up front and $1,500 more shortly afterwards. Wayne ended up living off government welfare whilst today 10% of Apple’s stock is worth approximately $300 billion.

Jobs negotiated a deal to sell 50 Apple I circuit boards for $25,000 to the ambitious owner of three local computer stores called Byte Shop. He scrambled to get the money together to buy the parts and enlisted his sister Patty, Daniel Kottke, and Elizabeth Holmes to help assemble them in his parents’ garage. They managed to create 100 boards with the $25,000 they anticipated getting from Byte Shop. They sold the remaining 50 boards to friends and members of the Homebrew Computer Club and used the money to build another 100 units whilst Wozniak designed a successor – the Apple II.

Up to this point, computers had been used mainly by hobbyists who enjoyed assembling them themselves, but Jobs wanted to aim for the mass market. He believed that they should come as a complete package with a case, a built-in keyboard, and end-to-end integration from the power supply to the software – in other words, they should be ready to use straight out of the box. So, he started turning the new design that Wozniak was developing into a fully integrated product.

To finance the Apple II, he tried to find investors. He offered Atari founder, Nolan Bushnell, a third of the company for $50,000 but he declined. Today, 33.3% of Apple’s stock is worth approximately $1 trillion. Bushnell later said, ‘It’s kind of fun to think about that, when I’m not crying.’ However, Bushnell did recommend the founder of Sequoia Capital, Don Valentine, to Jobs. Valentine was concerned that Jobs was still trying to sell products to individual stores, one by one. However, he agreed to invest if Jobs accepted a partner who understood marketing and could create a business plan. Jobs agreed and Mike Markkula joined Apple and drafted a business plan for the company.

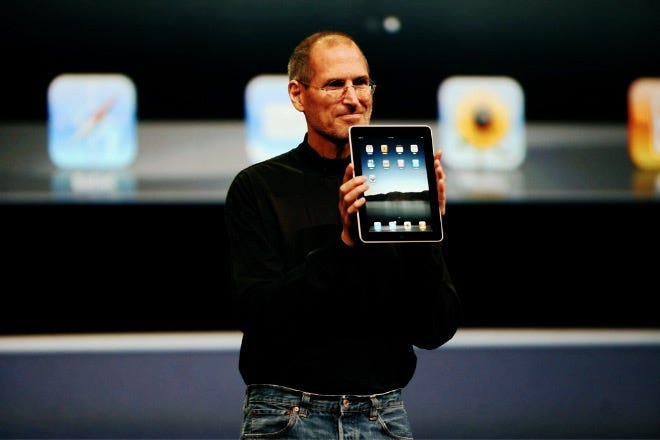

Markkula wrote a manifesto explaining how Apple should be run called ‘The Apple Marketing Philosophy’. The three main principles were ‘empathy’, ‘focus’, and ‘impute’. Empathy meant understanding the customer’s needs, focus meant working on a small number of very important opportunities, and impute meant imbuing every aspect of the company and its products with the qualities the company believed in. Jobs internalised these principles and by the end of his career he was completely attuned with consumer needs, relentlessly focused on creating a small number of revolutionary products and absolutely obsessed with embedding Apple’s values into everything they did. Thirty years later, Jobs said ‘When you open the box of an iPhone or iPad, we want that tactile experience to set the tone for how you perceive that product. Mike taught me that.’

He saw some Intel ads he liked in a magazine. He called up Intel and found they were done by publicist Regis McKenna. He kept calling McKenna until he agreed to a meeting and eventually convinced him to work with Apple. McKenna hired Rob Janoff to design a new logo for the company. He created two proposals and Jobs chose the iconic apple with a bite taken out.

The Apple II was released in 1977 and displayed at the West Coast Computer Faire. Jobs obsessed over how the Apple II’s launch could impute Apple’s desired qualities. He paid $5,000 for a booth at the front of the hall, covered the display table with black velvet and created a large backlit Plexiglass sign with Apple’s new logo on it. When the plastic cases of the Apple IIs arrived blemished, he was furious and demanded that they were sanded and polished. They displayed the only three Apple IIs which had been finished but piled up empty boxes to create the impression that there were more. They sold 300 units at the fair and it was only after this that Apple moved out of Paul and Clara Jobs’s garage.

As the company grew, he became increasingly abusive and tyrannical. Randy Wiggington, a younger programmer at Apple who had only just left school, recalled ‘Steve would come in, take a quick look at what I had done, and tell me it was shit without having any idea what it was or why I had done it.’ This, combined with his persistent personal hygiene problems which had now escalated to soaking his feet in the toilet to ‘relieve stress’, led the confrontation-averse Markkula to appoint Mike Scott as CEO of Apple in 1977 to control him. During their first meeting, Scott told Jobs to wash more often and Jobs responded by telling Scott to read one of his fruitarian diet books and lose some weight which set the tone for the rest of their relationship.

The Apple II went on to sell six million units over the next sixteen years and helped to launch the personal computer industry. Wozniak designed the circuit board and wrote the software, but Jobs turned it into a marketable product. He insisted that it be integrated from end to end so it was ready to work straight out of the box, agonised over the design to make sure it looked slick and eye-catching and created the company that was able to build, market, and ship it at scale. However, Wozniak got most of the credit and Jobs’s irritation motivated him to build a successor which would be recognised as his.

Lisa

When Chrisann returned from a spiritual trip to India in 1977, she and Jobs began going out again. She moved in with Jobs and Daniel Kottke and within a few months she was pregnant. Jobs was strangely unmoved and largely ignored the situation. He admitted that he had been sleeping with her but denied the child was his. His friend, Greg Calhoun, was shocked by his reaction and later recalled, ‘There was a side to him that was frighteningly cold.’ In 1978, Chrisann gave birth to a daughter at Robert Friedland’s apple farm commune. Three days later, Jobs arrived, helped name his daughter Lisa and then left shortly afterwards. Strangely, when Chrisann became pregnant, they were both twenty-three – the same age his biological parents were when his mother became pregnant with him. However, despite the pain of his own adoption, he abandoned Lisa just like his parents had abandoned him.

Chrisann and Lisa soon ended up in a run-down house living off government welfare because Jobs wasn’t helping to provide for them and Chrisann didn’t want the ordeal of suing him for child support. Eventually, the county sued him to establish paternity. He chose to fight the case and asked Kottke to testify that he had never seen him in bed with Chrisann, whilst his lawyers tried to find evidence that she had been sleeping with other men. The following year, to Chrisann’s surprise he suddenly agreed to take a paternity test. However, he knew that Apple was about to be taken public and wanted the child support settled before he became a multi-millionaire. The DNA test established that there was a 94.41% probability that Jobs was Lisa’s father. He was ordered to pay $385 a month in child support, sign an agreement admitting paternity, and reimburse the money that the county had paid out in welfare. He was given visitation rights but didn’t exercise them for many years. Despite the DNA test results, he continued to tell people that Lisa wasn’t definitely his. He told the Apple board that there was ‘a large probability that he wasn’t the father’ and he told a reporter that when you analysed the statistics ‘28% of the male population in the United States could be the father.’

Xerox PARC

He was desperate to design a new computer that would be as revolutionary as the Apple II but which would be seen as his masterpiece, not Wozniak’s. In 1979, he agreed a deal to sell 100,000 shares to Xerox at $10 a share in return for seeing the technology Xerox was developing at their Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). The engineers at PARC had managed to replace the cumbersome and uninviting command lines and DOS prompt system used on computers at the time with an intuitive visual layout, known as a graphical user interface (GUI) along with a mouse to move a cursor around the screen – essentially, the ‘desktop’ system we use today. To design the GUI, they had created a revolutionary new system for rendering graphics called bitmapping which also enabled a wide range of additional functions. One of the two PARC engineers showing him around, Larry Tesler, was keen to show off what they’d created but the other, Adele Goldberg, was angry that Xerox had agreed to show Apple their research. Goldberg managed to hide most of it from him but he was persistent and called up Xerox headquarters to complain. He was invited back the next day and shown more but Goldberg still tried to conceal the most cutting-edge work from him and he called up again to complain. Eventually, Goldberg got a call telling her to show him everything and angrily she stormed out. When he saw the GUI and bitmapping, he realised that this was the revolutionary technology he needed to build his masterpiece and he jumped around the room screaming in excitement. Jobs was unapologetic about using the PARC technology, ‘Picasso had a saying – “good artists copy, great artists steal” – and we have always been shameless about stealing great ideas.’

In 1981, Xerox released their own computer using the technology they had created called the Xerox Star but it was a commercial failure.

Daniel Kottke

When Apple went public in 1980, he became worth $256 million. Daniel Kottke had been one of his best friends since university, and employee #12 at Apple who had helped assemble the original Apple I boards when the company was still being run out of Paul and Clara Jobs’s garage but he wasn’t given any stock options. Kottke asked Jobs why several times but he kept brushing him off. Finally, Kottke decided to confront him about it but when he got into his office, Jobs suddenly became so cold that Kottke started to cry. Kottke recollected, ‘Our friendship was all gone. It was so sad.’ Rod Holt suggested to Jobs that they give Kottke some of their own options and offered, ‘Whatever you give him, I will match it.’ He replied, ‘Okay. I will give him zero.’ Apple engineer, Andy Hertzfeld later said of Jobs, ‘Steve is the opposite of loyal. He’s anti-loyal. He has to abandon the people he is close to.’

The Lisa and the Macintosh

Jobs began designing a successor to the Apple II and named the project Lisa. He later acknowledged that it was named after his daughter but at the time he worked with Regis McKenna to create the meaningless acronym ‘Local Integrated Systems Architecture’ as an official explanation of the name.

There was an internal battle over the Lisa. Jobs wanted a cheap and simple product for the general public whereas other engineers wanted a product for the corporate market. Markkula and Scott were worried about Jobs’s disruptive influence, so they took him off the Lisa project. At the time, engineer Jef Raskin developing a cheap computer for the general public which he had named ‘Macintosh’ after his favourite type of apple and when he was kicked off the Lisa project, Jobs turned to the Macintosh project instead. He didn’t like Raskin, describing him as ‘a shithead who sucks’, and they clashed over how to approach the Macintosh. Although they both wanted to create a lean computer for the masses, Raskin wanted to start by determining the combination of price and functionality that would appeal to the mass market whereas Jobs wanted to make a product that was ‘insanely great’ without any consideration of its price. Jobs’s petulance angered Raskin and other members of his team. In 1981, Raskin sent a memo to Scott titled ‘Working for/with Steve Jobs’:

‘He is a dreadful manager…I have always liked Steve, but I have found it impossible to work for him…Jobs regularly misses appointments. This is so well-known as to be almost a running joke…He acts without thinking and with bad judgment…He does not give credit where due…Very often, when told of a new idea, he will immediately attack it and say that it is worthless or even stupid, and tell you that it was a waste of time to work on it. This alone is bad management, but if the idea is a good one he will soon be telling people about it as though it was his own.’

In 1981, Scott gave Jobs control of the Macintosh project to keep him occupied and Raskin was told to take a leave of absence. Raskin was hired by Canon to build the computer he had envisioned. This became the Canon Cat which was a commercial failure when it was released in 1987.

John Sculley

In 1981, Scott was fired as CEO and Markkula searched for a replacement. One of the candidates was Pepsi president, John Sculley who had a reputation as a brilliant marketer. Jobs and Sculley met several times and grew strangely enamoured of each other. Sculley explained to Jobs how Pepsi’s marketing campaigns portrayed Pepsi as selling a lifestyle rather than just a product, whilst their promotional campaigns generated massive buzz ahead of product releases. Jobs was desperate to do both of those things at Apple and was determined that Sculley should become CEO. Sculley was seduced by Jobs’s charisma and passion and he began to flatter himself that he shared aspects of Jobs’s maverick genius. Jobs asked Sculley to join Apple as CEO but he was reluctant to leave Pepsi, so he declined offering to act as a mentor instead. In response Jobs challenged him, ‘Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water or do you want a chance to change the world?’ Sculley realised that he couldn’t say no and he became Apple CEO in 1983.

When Sculley first arrived at Apple, his relationship with Jobs became even closer. They spoke several times a day and repeatedly told each other how happy they were to be working together. However, over time their impressions of each other started to diverge. Whilst Sculley continued to find flattering similarities between them, Jobs began to realise that Sculley wasn’t as bright or as competent as he’d thought he was. Jobs sensed Sculley’s eagerness for his approval and, as he used this to manipulate him, he lost more and more respect for him.

Creating the Mac

Jobs began recruiting the best engineers he could find to work on the Macintosh. Andy Hertzfeld was developing software for the Apple II when Jobs approached him and asked, ‘Are you any good? We only want really good people working on the Mac and I’m not sure you’re good enough.’ Hertzfeld told him he was, and Jobs left. Later that day, Jobs returned and said, ‘I’ve got good news for you. You’re working on the Mac team now. Come with me.’ Hertzfeld told him he needed a couple of days to work on the software he was writing so it was ready to be handed over to someone else. Jobs replied, ‘What’s more important than working on the Macintosh? You’re just wasting your time with that! Who cares about the Apple II? The Apple II will be dead in a few years. The Macintosh is the future of Apple, and you’re going to start on it now!’ He then pulled the power cord out of the back of Hertzfeld’s computer, deleting the code he had been working on, and drove Hertzfeld and his computer to the offices where the Macintosh was being built. After the Xerox Star flopped in 1981, Jobs called one of the hardware designers, Bob Belleville, and said ‘Everything you’ve ever done in your life is shit, so why don’t you come work for me?’ Belleville did, along with Larry Tesler. Another PARC engineer, Bruce Horn, considered going to Apple as well but ended up getting a much better paid offer from another company. Jobs called him on a Friday night and said, ‘You have to come into Apple tomorrow morning. I have a lot of stuff to show you.’ Horn went and Jobs sold him on the project. ‘Steve was so passionate about building this amazing device that would change the world. By sheer force of his personality, he changed my mind. He wanted me to see that this whole thing was going to happen and it was thought out from end to end. “Wow”, I said, “I don’t see that kind of passion every day.” So, I signed up.’ Jobs later explained the importance of hiring the best people, ‘I’ve learned over the years that when you have really good people you don’t have to baby them. By expecting them to do great things, you can get them to do great things. The original Mac team taught me that A players like to work together, and they don’t like it if you tolerate B work. Ask any member of that Mac team. They will tell you it was worth the pain.’ The Mac team also included Joanna Hoffman, Bud Tribble, Debi Coleman, Bill Atkinson, Burrell Smith, and Larry Kenyon.

Jobs could be highly delusional, and the team named this his ‘reality distortion field’. When he was exposed to unwelcome facts, he seemed to be genuinely incapable of accepting them. For example, when Chrisann became pregnant he became detached from the obvious reality that he was the father, even after a DNA test proved he was. He was able to use his charisma to convince other people of his delusions which could have both a positive and a negative effect. On the one hand, it made it impossible to be realistic about engineering trade-offs and deadlines but on the other it pushed people to do things they didn’t think were possible. Bud Tribble, a software engineer on the Mac team described it, ‘In his presence, reality is malleable. He can convince anyone of practically anything. It wears off when he’s not around, but it makes it hard to have realistic schedules. It was dangerous to get caught in Steve’s distortion field, but it was what led him to actually be able to change reality.’

He was also incredibly emotionally attuned, and he could read people’s strengths and weaknesses and use their insecurities to manipulate them. Joanna Hoffman explained, ‘He had the uncanny capacity to know exactly what your weak point is, know what will make you feel small, to make you cringe. Knowing that he can crush you makes you feel weakened and eager for his approval, so then he can elevate you and put you on a pedestal and own you.’ Counterintuitively, many people found his demoralising style inspiring because they could see how much he cared about creating a great product. Debi Coleman recalled, ‘He would shout at a meeting, “You asshole, you never do anything right!” It was like an hourly occurrence. Yet I consider myself the absolute luckiest person in the world to have worked with him.’

One day he told an engineer that what he was working on was shit. The engineer replied that it was actually the best way and when he explained the engineering trade-offs he’d made, Jobs backed down. Another engineer, Bill Atkinson, said, ‘We learned to interpret “This is shit” to actually be a question that means, “Tell me why this is the best way to do to it.”’ However, the engineer eventually found a better approach. ‘He did it better because Steve had challenged him, which shows you can push back on him but you should also listen, for he’s usually right.’

As Raskin had earlier discovered, Jobs also frequently took credit for other people’s ideas. Bud Tribble recalled, ‘If you tell him a new idea, he’ll usually tell you that he thinks it’s stupid. But then, if he actually likes it, exactly one week later, he’ll come back to you and propose your idea to you, as if he thought of it.’ Bruce Horn had the same experience, ‘One week I’d tell him about an idea that I had, and he would say it was crazy. The next week, he’d come and say, “Hey, I have this great idea” – and it would be my idea! You’d call him on it and say, “Steve, I told you that a week ago,” and he’d say, “Yeah, yeah, yeah” and just move right along.’

Jobs wanted every aspect of the Mac, from to the case to the on-screen graphics, and the packaging to the circuitry, to be sleek and minimalist. He insisted that the GUI should use rectangles with rounded edges even though they were incredibly difficult to code. He even wanted the parts of the Mac which no one could see to be beautiful and he had the memory chips moved on the circuit board because he believed the arrangement was ugly. When the design of the Mac case had been finalised, he asked the team to sign their names on a piece of paper and had the signatures engraved on the inside of the case. He also had bespoke screws created to seal the Mac case so that they couldn’t be opened with a regular screwdriver to prevent anyone adding or changing the features (or seeing the signatures engraved on the inside). Jobs wanted a consistent design style for all of Apple’s products and in 1982 he hired Hartmut Esslinger as Apple’s designer.

In 1983, it became clear that the disk drive they’d developed was defective. Belleville proposed two solutions – either use a different disk drive that Sony had developed or use a clone of it that Sony had licensed to another Japanese company called Alps Electronics Co. The disk drives would be the same but the Alps version would be much cheaper. Jobs and Belleville flew to Japan to visit the Sony and Alps factories and Jobs was incredibly rude to his impeccably mannered Japanese hosts. Alps didn’t even have a working prototype ready and Belleville knew they wouldn’t be ready in time for the Macintosh launch. Sony had the disk drive ready but Jobs hated the factory and decided to work with Alps despite Belleville’s objections. Belleville decided to secretly work with Sony anyway so that they would have another disk-drive ready when Alps inevitably failed to deliver. So, Sony sent an engineer, Hidetoshi Komoto, to Apple’s offices in Cupertino to integrate the disk-drive with the rest of the Macintosh’s components. Whenever Jobs visited the engineering department they hid Komoto so that Jobs didn’t realise what they were doing. Jobs actually recognised Komoto at a newsstand in Cupertino but didn’t suspect anything. One day Jobs arrived unexpectedly and the engineers bundled Komoto into a storage closet and told him to stay there until Jobs left. When they let him out they apologised and Komoto replied, ‘No problem, but American business practices, they are very strange. Very strange.’ When it became clear that the Alps disk wasn’t going to be ready in time, Markkula was angry and pressed Jobs on what he was going to do. Belleville interrupted and said he had an alternative to the Alps disk which would be ready in time for the launch. Jobs was confused but then suddenly realised why he’d seen Sony’s top disk designer in Cupertino. With a big grin on his face, he turned to Belleville and said, ‘You son of a bitch!’

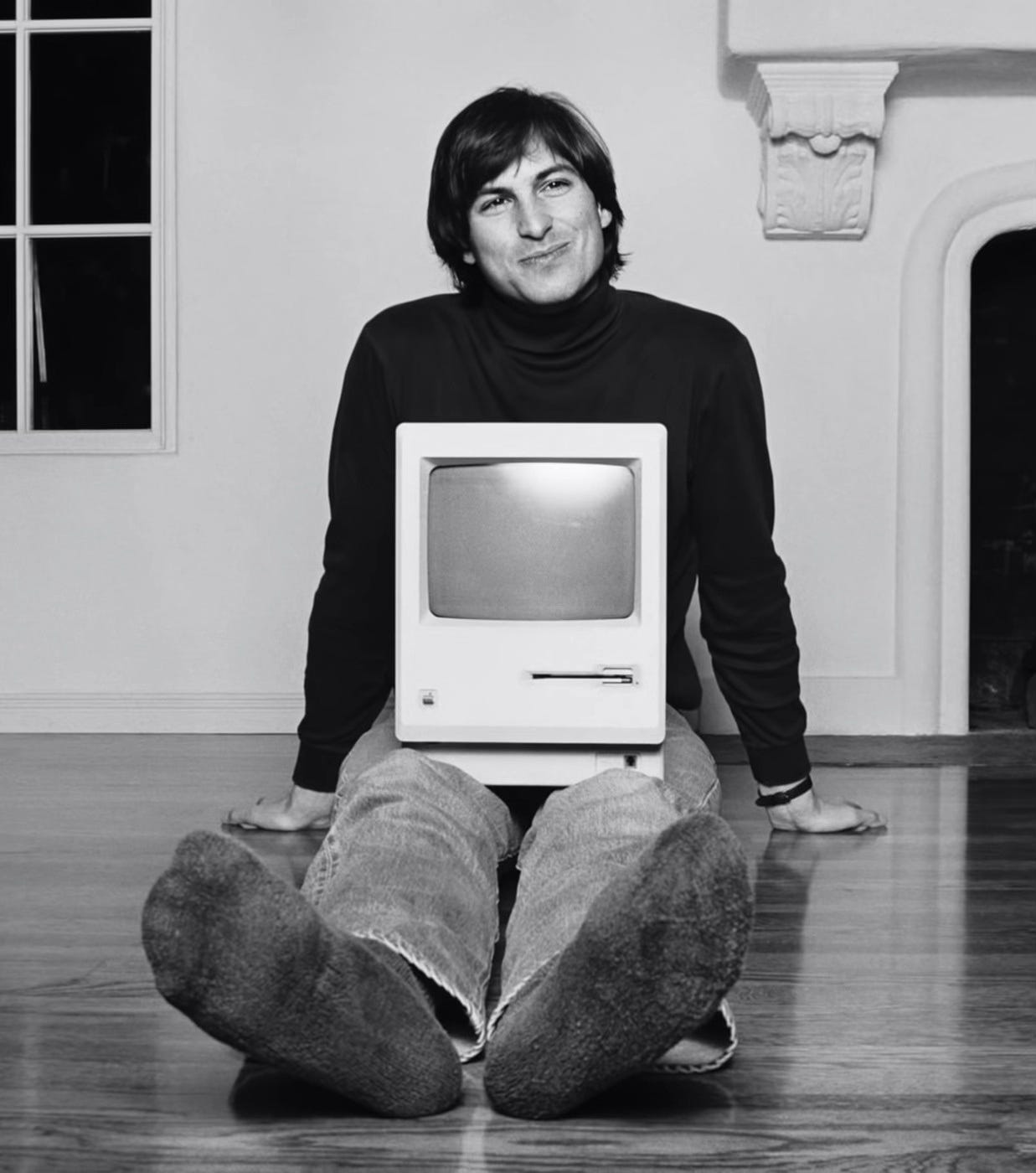

Ultimately, the Macintosh was a great product but way over budget and way behind schedule because of Jobs’s uncompromising attitude and complete refusal to accept trade-offs.

The Mac Launch

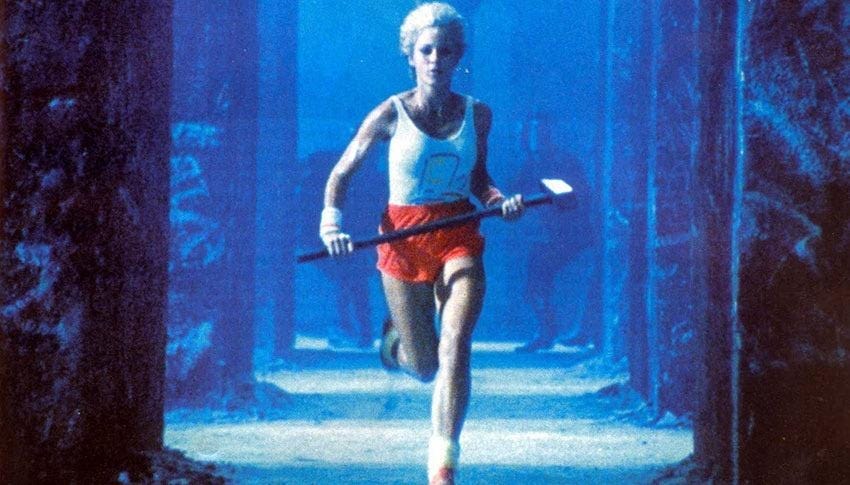

Jobs wanted to launch the Mac with an advert that was as revolutionary as the computer itself and he hired Lee Clow, the Creative Director of advertising agency Chiat/Day, to create one. The result was ‘1984’, a minute-long sci-fi themed ad directed by Ridley Scott. The Mac was being released in 1984 and the advert referenced George Orwell’s dystopian novel by showing a bleak totalitarian society being symbolically liberated by the Mac. In the advert, a woman in a Mac-covered tank top outruns Orwellian thought police and throws a sledgehammer through a screen playing a speech by Big Brother. The advert then closed with the line ‘On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like “1984”.’ It played for the first time during the 1983 Superbowl and became a viral sensation, being covered as an item on all the national news stations in the US.

He launched the Mac with a dramatic public presentation. He walked to the centre of the stage and revealed the computer from underneath a black cloth. The word ‘MACINTOSH’ scrolled across the screen and the words ‘Insanely great’ appeared in a handwritten font beneath – an amazing graphical display at the time. He clicked the mouse and an electronic voice began, ‘Hello. I’m Macintosh. It sure is great to get out of that bag.’ The presentation got a five-minute standing ovation.

When he was asked what market research he had done during the development of the Mac, he replied, ‘Did Alexander Graham Bell do any market research before he invented the telephone?’

After the Mac

The Lisa was launched in 1983 and was a commercial failure. After the Macintosh was released in 1984, the two teams were merged and Jobs was put in charge. He immediately put members of the Macintosh into senior positions and told the Lisa team, ‘You guys failed. You’re a B team. B players. Too many people here are B or C team players.’ and fired 25% of them.

The Mac sold very well at first but sales fell to around 10% of the team’s projections when it became clear how slow and underpowered it was. Jobs travelled to Europe to meet the sales teams selling the Mac and insulted most of them. In a desperate move to boost sales, he tweaked some of the unsold Lisas, and rebranded them as Mac XLs. The follow-up to the iconic 1984 ad was called ‘Lemmings’ and depicted corporate managers who’d bought an IBM marching off a cliff. It insulted a group Apple were trying to reach and was received very badly. Andy Hertzfeld took a leave of absence to recover from the intensity of the Mac project and he found out that Jobs was withholding a $50,000 bonus to try and force him to come back. Hertzfeld confronted Jobs and told him that he wouldn’t come back out of principle if he withheld the bonus. Jobs relented but it had angered Hertzfeld. Shortly before he was due to return, Hertzfeld spoke to Jobs about the morale problems within the new Macintosh team. Jobs angrily told him that there were no problems and that he was having the best time of his life. Hertzfeld replied that if Jobs didn’t realise that there was a problem he didn’t want to come back because ‘the Mac team that I want to come back to doesn’t even exist anymore.’ Jobs replied, ‘The Mac team had to grow up, and so do you. I want you to come back but if you don’t want to that’s up to you. You don’t matter as much as you think you do, anyway.’ So Hertzfeld didn’t come back. Software engineer Burrell Smith was determined to leave but he knew how hard it was to resist Jobs’s charisma and was worried that he would convince him to stay. Eventually, he decided to make Jobs sack him by walking into his office and urinating on his desk. (American business practices are very strange, indeed.) There was an office sweepstake on whether Smith would actually do it and when Smith finally worked up enough courage to enter Jobs’s office, he was surprised to find Jobs grinning back at him. ‘Are you gonna do it? Are you really gonna do it?’ Smith told him he would if he had to. Jobs said he didn’t need to and accepted his resignation. Bruce Horn resigned next and when he went to went to say goodbye to Jobs, Jobs told him, ‘Everything that’s wrong with the Mac is your fault.’ Horn replied, ‘Well, actually, Steve, a lot of things that are right with the Mac are my fault and I had to fight like crazy to get those things in.’ Jobs agreed and offered him 15,000 shares to stay which Horn refused. Wozniak left Apple in 1984 in frustration at how the Apple II team was treated. The Apple II was responsible for 70% of Apple’s sales but Wozniak felt like they were treated as an irrelevance. In an interview he said, ‘Apple’s direction has been horrendously wrong for five years.’ Wozniak wanted to leave amicably, so he agreed to continue working at Apple part-time representing the company at events and tradeshows. However, Jobs discovered that Apple’s designer, Hartmut Esslinger, was working with a new company Wozniak had founded and he triggered a clause in Apple’s contract with Esslinger that prevented him working with competitors and had the designs he’d done for Wozniak destroyed.

Tensions between Jobs and Sculley grew. Jobs was frustrated that Sculley didn’t care about great products whilst Sculley was uncomfortable with the way Jobs treated people. Sculley offered Jobs a new role leading research and development department called ‘Apple Labs’ away from Apple’s main offices. Jobs was tempted but declined. In 1985, with senior managers increasingly complaining about him, Sculley decided to remove Jobs as head of the Macintosh team and replace him with Jean-Louis Gassée, the head of Apple’s French sales division. When Sculley told him that he was going to recommend to the board that he should be taken off the Macintosh project, Jobs started crying. Sculley urged him not to resist and to accept the R&D role he’d been offered earlier. Jobs behaved erratically as he struggled to process the news. He alternated between telling people how excited he was about running Apple Labs and asking them to help him oust Sculley as CEO. The board authorised Sculley to remove Jobs as head of the Macintosh team and Jobs asked for the transition to happen slowly – over the span of a few months – which Sculley agreed. Shortly afterwards, he asked Sculley to give him more time to prove himself as leader of the Macintosh team and when Sculley refused, Jobs told him that he should resign as CEO. Two weeks later at a quarterly review Jobs presented the new projects the Macintosh team were working on, many of which were behind schedule. Despite Sculley’s criticism of the team’s performance Jobs publicly asked once again to be given another chance to prove himself. Sculley refused again and that night Jobs decided to organise a coup to remove him. Sculley was due to fly to China for a business trip and Jobs decided to put his plan into action whilst Sculley was away and unable to stop it.

The day before Sculley’s trip, Jobs told the staff most loyal to him about his plan. One of them was HR director, Jay Elliot, who had spoken to board members and knew that most of them supported Sculley. He told Jobs the plot would fail but Jobs ignored him. Bizarrely, Jobs also told Gassée, the man that Sculley had lined up to replace him as head of the Mac team. That evening Gassée told Sculley what Jobs was planning and Sculley cancelled his trip to China. At an executive staff meeting the next morning, Sculley asked Jobs directly whether he was plotting to remove him. Jobs told Sculley that he didn’t know how to run the company and he should resign as CEO. Jobs then claimed that he could run Apple better than him. Sculley asked senior staff present to vote on who they thought should run the company. Jobs was stunned as, one by one, they opted for Sculley. Jobs left the room, returned to his office, and cried. Two days later, Jobs and Sculley met and Jobs again asked Sculley to let him retain an operational role, which Sculley refused. Incredibly, Jobs then seriously suggested that Sculley should make him CEO and then resign from Apple. Sculley couldn’t believe how sincere Jobs seemed. Later that day, Jobs invited Markkula to dinner with the loyal staff from the Mac team and they tried to persuade Markkula to back Jobs over Sculley. Markkula listened to them but declined to support Jobs. Markkula told Sculley about the meeting and Sculley asked the board to authorise him to sack Jobs. They did and when he went to Jobs’s office and told him, Jobs again started to cry. Jobs was allowed to remain chairman of the company but the offer of running Apple Labs was withdrawn.

Jobs was deeply depressed and became reclusive. He sat at home with the blinds drawn ruminating over what had happened. Eventually, he went travelling to Italy with his girlfriend, Tina Redse. He loved the architecture and was particularly inspired by the bluish-grey Pietra Serena paving stones in Florence.

Pixar & NeXT

After being fired from Apple in 1985, Jobs founded two new companies – Pixar and NeXT. Jobs sold all but one of his Apple shares (so he could continue to attend shareholder meetings) for around $100 million.

Jobs’s Biological Family

In the early 1980s, Jobs began searching for his biological parents. He found the name of the doctor who had delivered him on his birth certificate and he called him up. The doctor told him all his records had been destroyed in a fire but that wasn’t true. The doctor wrote a letter and sealed it in an envelope with ‘To be delivered to Steve Jobs on my death’ written on the front. He died shortly afterwards and Jobs received a letter that told him his biological mother was called Joanne Schieble. Jobs then hired a private investigator who found her. She was now called Joanne Simpson and she was living in Los Angeles. Jobs was uncharacteristically considerate and didn’t tell Paul and Clara that he was searching for his biological parents because he didn’t want to upset them by suggesting that he didn’t think they were his real parents. He waited until Clara died in 1986 before he contacted his biological mother. He called her, explained who he was and arranged to meet her in LA. She became very emotional and apologised repeatedly. She told him that she had been pressured into putting him up for adoption and had felt guilty ever since. He reassured her that he understood and that everything had worked out fine. She told him that he had a biological sister called Mona who was an aspiring novelist and arranged for them to meet. Their father, Abdulfattah Jandali, had abandoned Joanne and Mona when Mona was five. Mona found him again and told Jobs but Jobs wasn’t interested in meeting him. Jobs was angry with his father for abandoning Mona despite the fact he too had abandoned a daughter. Mona found out that their father was working in a small restaurant but Jobs asked Mona not to tell Jandali about him. She didn’t but in a bizarre twist Jandali revealed that he had previously owned an expensive restaurant in San Jose in which he had entertained many famous people from Silicon Valley, including Steve Jobs. Mona told Jobs and he recalled going to the restaurant and even shaking hands with his biological father. Jobs reiterated that he didn’t want Mona to tell Jandali about him and she didn’t. Years later, Jandali found out when he read online that Jobs was Mona’s biological brother but he never tried to contact him.

Tina Redse

In 1985, Jobs met Tina Redse and they developed an intense and passionate relationship. In public, they would be both very affectionate and very argumentative. Redse was shocked by how uncaring he was and she found it incredibly painful to love someone who was so self-centred. She once scrawled ‘Neglect is a form of abuse’ on the wall in the hallway leading to their bedroom. In 1989, he proposed to Redse but she declined and they separated. She had grown up in a volatile household and her relationship with Jobs reminded her too much of it. After they broke up, Redse co-founded a charity to help people with mental illnesses and one day she came across a psychiatric manual which included a section about Narcissistic Personality Disorder which she realised perfectly described Jobs’s self-centredness and incapacity for empathy. Later in his life – even after he married – Jobs would openly pine for her.

Lisa

During Lisa’s childhood, Jobs would occasionally visit the house he’d bought for her and Chrisann to live in but he talked mostly to Chrisann. However, these visits became more frequent and by 1986 he was seeing Lisa regularly. They grew closer but he was erratic and would alternate between being very affectionate and very distant with her. In 1992, Chrisann’s mental health declined and Lisa moved in with her father and lived there until she was eighteen. Chrisann accused him of deliberately undermining her mental health to get custody of Lisa. Lisa and her father continued to have a tumultuous relationship. Lisa could be as temperamental and stubborn as her father and the remainder of their relationship was rocky with long periods without contact. When Lisa went to university, their arguments eventually led to him refusing to pay her tuition. Andy Hertzfeld lent her the money instead. Jobs was angry but paid him back the next day. Later, Chrisann needed money to pay for treatment for a sinus infection and dental problems but Jobs refused to help her and Lisa stopped talking to him for several years. In 2010, he was going through a box of photos with Isaacson and found one of him visiting Lisa when she was young. He reflected that he should probably have visited her more. At the time, he was terminally ill and he and Lisa had not spoken in almost a year but when Isaacson suggested that he should reach out to her, Jobs looked at him uncomprehendingly for a moment before continuing to look through the photos.

Starting a Family

In October 1989, Jobs met Laurene Powell. On New Year’s Day in 1990, he proposed and she accepted. He would alternate between being affectionate and distant with her and in September 1990 she broke up with him and he tried to rekindle his relationship with Redse. However, a month later he presented Laurene with a ring and she moved back in. In December 1990, Laurene got pregnant and they married in March 1991. Jobs did not have many friends and didn’t have a best man. They had three children, a son, Reed, born in 1991, and two daughters, Erin and Eve, born in 1995 and 1998, respectively.

NeXT

In 1985, shortly after leaving Apple Jobs founded NeXT, a company dedicated to creating powerful computers for higher education. He was still Apple chairman and he told the board his plans but assured them that the company wouldn’t rival Apple and that he wouldn’t take any senior staff with him. The board wished him well and even proposed taking a 10% stake in NeXT. However, NeXT rivalled Apple in the further education market and Jobs took five senior employees with him. When the board found out they were furious. Many issued public statements condemning him and he resigned as chairman. A few days after his resignation, the board sued him for breaching his fiduciary duty as Apple chairman by founding a competing company, making a product that he knew Apple was developing and luring away key employees.

Jobs wanted Hartmut Esslinger to design for NeXT despite the clause in his contract with Apple preventing him from working with competitors, which Jobs had invoked to stop him working with Wozniak. Even though he was being sued by Apple, he sent a letter to board member Al Eisenstat asking him to let Esslinger work with NeXT. Incredibly, he suggested that if Esslinger designed NeXT’s products it would be less likely that they would be similar to Apple’s. He argued that because he didn’t know which products Apple were planning to develop, if another company designed NeXT’s products they may end up being similar. However, since Esslinger knew which products Apple were producing, he could ensure that NeXT’s were different. Eisenstat was stunned by Jobs’s audacity and sent a scathing reply. Jobs realised that in order to work with Esslinger he needed to settle the suit with Apple. He agreed that NeXT’s products would be marketed as a high-end computer, sold directly to colleges and universities, wouldn’t use an operating system compatible with Apple and wouldn’t be released before March 1987. After the settlement, Jobs persuaded Esslinger to wind down his contract with Apple which left him free to work with NeXT in 1986.

Jobs wanted Paul Rand to design a logo for NeXT. Rand was under contract at IBM and his supervisors said he couldn’t design anything for another computer company. Jobs called both the CEO and the vice chairman to ask them to make an exception. They refused but he kept calling until they finally relented. Jobs paid Rand $100,000 for the design before NeXT even had a product.

Jobs wanted NeXT’s computer to be a perfect one-foot cube in matte black but this created problems. The matte black would show blemishes more clearly, the shape made it difficult to arrange the circuit boards and a case with perfect 90-degree angles was hard to manufacture because it was difficult to get out of a mould. The first set of cases had a small line on them from the mould. Jobs flew to the factory in Chicago and forced the company to buy a $150,000 sanding machine to remove the lines on the mould and then demanded that they replace the cases they’d sent. Again, Jobs wanted the design to extend to the parts of the product which couldn’t be seen and insisted that expensive plated screws and the matte black be used in the inside of the case.

Jobs had NeXT’s headquarters in Palo Alto completely renovated even though they were brand new. When they moved to a bigger building a few years later Jobs did the same thing again and even insisted the that the lifts were moved. He commissioned I. M. Pei to design a glass staircase that appeared to float unsupported. The design was later featured in most Apple stores.

Jobs was just as tyrannical as he had been at Apple. One engineer, David Paulsen, quit after ten months of working ninety-hour weeks when Jobs came in one day and ‘told us how unimpressed he was with what we were doing.’ Jobs explained why he did this, ‘Part of my responsibility is to be a yardstick of quality. Some people aren’t used to an environment where excellence is expected.’

The NeXT Computer was announced in 1988. Jobs gave a dramatic presentation like the Macintosh launch in 1984. Even though neither the hardware nor the software was finished, Jobs decided to demonstrate the computer live rather than use a simulation which many in the team wanted him to. The computer was priced at $6,500. The accompanying printer cost $2,000 and the external hard drive that was advisable due to the slowness of its optical disk cost $2,500. The panel of academic advisors at NeXT had pushed for a price between $2,000 and $3,000, which they believed Jobs had promised to deliver. Jobs then revealed that only the ‘0.9’ version was being released because the hardware and software wasn’t finished. In other words, the computer wasn’t actually ready yet and he couldn’t say when it would be finished. When a reporter asked him why the computer was going to be late, he replied, ‘It’s not late. It’s five years ahead of its time.’ It was eventually released in mid-1989 and it was a commercial failure.

Pixar

In 1985, Jobs visited George Lucas’s film studio and met Ed Catmull and John Lasseter. Catmull was running the computer division at Lucasfilm which made hardware and software for rendering digital images and Lasseter ran a department creating short computer animated films. Jobs recalled, ‘I was blown away, and I came back and tried to convince Sculley to buy it for Apple but the folks running Apple weren’t interested, and they were busy kicking me out anyway.’ George Lucas needed money to finance an expensive divorce and he asked Catmull to find a buyer for the division. Jobs bought 70% for $5 million and put another $5 million in as investment. He became the chairman, whilst Catmull and Lasseter ran the company day-to-day. They named the company Pixar after the most important piece of hardware they made, the Pixar Image Computer.

Employees were soon exposed to Jobs’s reality distortion field. Pixar’s marketing director, Pam Kerwin, described a meeting with him, ‘We would be nodding our heads and getting excited and say, “Yes, yes, this will be great!” and then he would leave and we would consider it for a moment and then say, “What the heck was he thinking?” He was so weirdly charismatic that you almost had to get deprogrammed after you talked to him.’

For the first few years Pixar’s hardware, software, and animated stories divisions haemorrhaged money and by 1988 Jobs had invested $50 million – more than half of what he got from his Apple shares. He ordered massive layoffs with no severance. Kerwin begged him to give at least two weeks’ notice and Jobs replied, ‘Okay, but the notice is retroactive from two weeks ago.’ Jobs loved the animated shorts and continued to fund them despite Pixar’s money trouble. He would brutally cut budgets and then Lasseter would ask for the saved money to be spent on another short film, and Jobs would agree.

In 1986, Lasseter produced a short film called Luxo Jr. which won the best film at SIG-GRAPH and was nominated for an Oscar. Jobs loved it and wanted to make more short films even though there was no obvious market for them. In 1988, Pixar released Tin Toy and it became the first computer animated film to win an Oscar. Lasseter was offered a senior position at Disney but declined. He told Catmull, ‘I can go to Disney and be a director, or I can stay here and make history.’

In the late 1980s, Pixar won a contract to provide hardware and software for the Disney animation department. The head of Disney’s film division, Jeffrey Katzenberg, invited Jobs to visit. As he was being shown round, he asked Katzenberg, ‘Is Disney happy with Pixar?’ and Katzenberg said they were. Jobs continued, ‘Do you think we at Pixar are happy with Disney?’ Katzenberg said he thought so but Jobs replied, ‘No, we’re not. We want to do a film with you. That would make us happy.’ Katzenberg liked the idea and invited the Pixar team for a discussion about working together on a film. Katzenberg and Jobs were both very stubborn and, as a result, the negotiations took months. Pixar was only avoiding bankruptcy because Jobs was subsidising the company personally, whereas Disney could afford to finance the film on its own and the deal they struck reflected that power imbalance. Disney got creative control, owned all rights to the film and its characters, had the option to make Pixar’s next two films, the right to make sequels with or without Pixar’s involvement and the right to terminate the project entirely for a small fee. In return, Pixar was entitled to 12.5% of the ticket sales.

The film they made together was Toy Story. Jobs was frustrated that Pixar was beholden to Disney and he decided to take the company public once the film was released to generate money so they would be in a position to renegotiate their deal. Toy Story was released in November 1995, and it was a massive success. Pixar was taken public a week later and Jobs’s shares became worth $1.2 billion. Crucially, Pixar had enough money to renegotiate their deal with Disney. Disney CEO Michael Eisner couldn’t believe Jobs’s audacity for wanting to renegotiate a three-film deal after only one film. Jobs threatened to go to another studio after the three films had been made and Eisner threatened to make sequels using the Toy Story characters without Pixar. Lasseter thought Disney’s animated films were awful and the thought of them making sequels with Pixar horrified him. He said, ‘It’s like you have these dear children and you have to give them up to be adopted by convicted child molesters.’ Ultimately, Eisner agreed that Pixar would contribute half of the budget for the films in return for half the profits and the films would be co-branded.

Return to Apple

When Jobs was fired from Apple in 1985, Sculley concluded that it wasn’t possible to sell high tech products to a mass market. Apple had remained highly profitable for a few years but the products which made the company successful weren’t improved and Microsoft released a series of popular operating systems which led them to dominate the market. Apple’s market share fell from 16% in the late 1980s to 4% in the mid 1990s, by which point it was losing hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

In 1994, Jobs visited Apple board member Gil Amelio and told him that he wanted to be Apple’s CEO. He told Amelio that he was the only person who could save Apple and asked him to help him return to the company. Jobs told him he had a plan to create a new generation of revolutionary products but Amelio was unimpressed and refused to help him.

At Christmas in 1995, Jobs’s friend and mentor, the billionaire Oracle founder Larry Ellison, suggested that he buy Apple and make Jobs the CEO. Jobs declined, ‘I decided I’m not a hostile-takeover kind of guy. If they had asked me to come back, it might have been different.’

In February 1996, Gil Amelio was made Apple’s new CEO. A few months later, Larry Ellison introduced Amelio to a journalist, Gina Smith, at a party and she asked him about Apple’s financial problems. He answered, ‘You know, Gina, Apple is like a ship. That ship is loaded with treasure, but there’s a hole in the ship and my job is to get everyone to row in the same direction.’ Smith was confused and replied, ‘Yeah, but what about the hole?’ Jobs recalled Ellison telling him the story, ‘We were in this sushi place and I literally fell off my chair laughing. He was just such a buffoon and he took himself so seriously. He insisted that everyone call him Dr. Amelio. That’s always a warning sign.’ During Amelio’s first year as CEO, Apple lost $1 billion.

In summer 1996, Amelio discovered that the operating system that Apple was developing to resolve networking and memory problems on its computers didn’t work. Amelio searched for another company to create an operating system and considered acquiring NeXT and have them produce the software. Jobs was desperate for the deal to go through – not only was NeXT haemorrhaging money but Jobs also realised that the acquisition gave him the opportunity to become Apple’s CEO. At Christmas in 1996, Jobs told Ellison that he could become CEO of Apple without Ellison having to buy it. He explained that if Apple bought NeXT he would get a seat on Apple’s board and then he would only be a step away from becoming CEO. Ellison was confused and replied, ‘Steve, there’s one thing I don’t understand. If we don’t buy the company, how can we make any money?’ Jobs placed a hand on his friend’s shoulder and said, ‘Larry, this is why it’s really important that I’m your friend. You don’t need any more money.’

In 1997, Apple acquired NeXT for $400 million. Jobs took $120 million in cash and $37 million in stock which he agreed not sell within the first six months. Amelio was aware of Jobs’s charisma and the how infectious his reality distortion field could be. He made a conscious effort to ‘move ahead with logic as my drill sergeant’ and ‘sidestep the charisma’ but during the negotiations Jobs made him ‘feel like a lifelong friend’ and Amelio was taken in by him. Jobs charmed Amelio and made him think that he was on his side and wanted them to work together. Like Sculley before him, Amelio admired Jobs and was desperate for his approval but Jobs undermined him by badmouthing him behind his back.

Despite what he’d told Ellison at Christmas, Jobs suddenly became deeply conflicted about how involved he wanted to be at Apple. Amelio offered him a full-time role leading the team designing Apple’s operating system but he declined. Amelio asked him what role he did want but he was evasive. When Amelio finally pressured him for an answer, Jobs chose ‘advisor to the chairman’ which Amelio accepted.

Exactly six months after Apple acquired NeXT, Jobs sold 1.5 million of his Apple shares. Amelio saw that the shares had been sold and, suspecting that it was Jobs, angrily challenged him about it. Jobs led him to believe that it wasn’t him that had sold them and Amelio released a statement to that effect. When the SEC filing came out, Amelio discovered it was Jobs and he finally realised that he wasn’t on his side after all.

Running Apple

In June 1997, Apple’s board fired Amelio and asked Jobs to become CEO. Despite clearly having a deep desire to run the company, he declined. He claimed it would be hard for him to be CEO of Apple and Pixar at the same time and that he wanted to spend time with his family. However, he’d been CEO of NeXT and Pixar simultaneously and he had always been much more focused on his work than his wife or children. Instead, it seems that he was unsure about whether Apple could be saved which unnerved him. Jobs agreed to join the board and spend a couple of days a week helping to hire a new CEO. However, his love of Apple and his domineering personality resulted in him taking control of the company anyway.

Jobs wanted to change the way stock options were priced to stop the exodus of Apple’s best employees. Whilst the change was technically legal, it was frowned upon and the board wanted to conduct a legal and financial review of the change which would take two months to complete. Jobs responded, ‘Are you nuts?! Guys, if you don’t want to do this I’m not coming back on Monday because I’ve got thousands of key decisions to make that are far more difficult than this and if you can’t throw your support behind this kind of decision I will fail.’ The next day the board relented. However, Jobs was so angry that he needed the approval of people he didn’t respect that he demanded that they all resign apart from the chairman, Ed Woolard. The board were incredulous – given that Jobs had continually refused to commit to be anything more than a part-time advisor to Apple whilst they searched for a permanent CEO, it seemed an unbelievable demand. However, they knew how desperate Apple’s situation was and they were exhausted from dealing with Jobs, so they did. Jobs then appointed a new board who would allow him to do what he wanted.

Jobs discontinued 70% of Apple’s product range. At a product review, he went to a white board and drew a horizontal line down the middle then a vertical line through it to create four quadrants. He wrote ‘Consumer’ and ‘Pro’ above each column and ‘Desktop’ and ‘Portable’ beside each row and announced they were going to create four great products – one for each quadrant.

Jobs laid off thousands of employees and replaced them with ‘A players’. He explained, ‘For most things in life, the range between best and average is 30% or so. The best airplane flight, the best meal, they may be 30% better than your average one. What I saw with Woz was someone who was fifty times better than the average engineer. He could have meetings in his head. The Mac team was an attempt to build a whole team like that, A players. People said they wouldn’t get along, they’d hate working with each other. But I realised that A players like to work with A players, they just didn’t like working with C players. At Pixar, it was a whole company of A players. When I got back to Apple, that’s what I decided to try and do. My role model was J. Robert Oppenheimer. I read about the type of people he sought for the atom bomb project. I wasn’t nearly as good as he was but that’s what I aspired to do.’

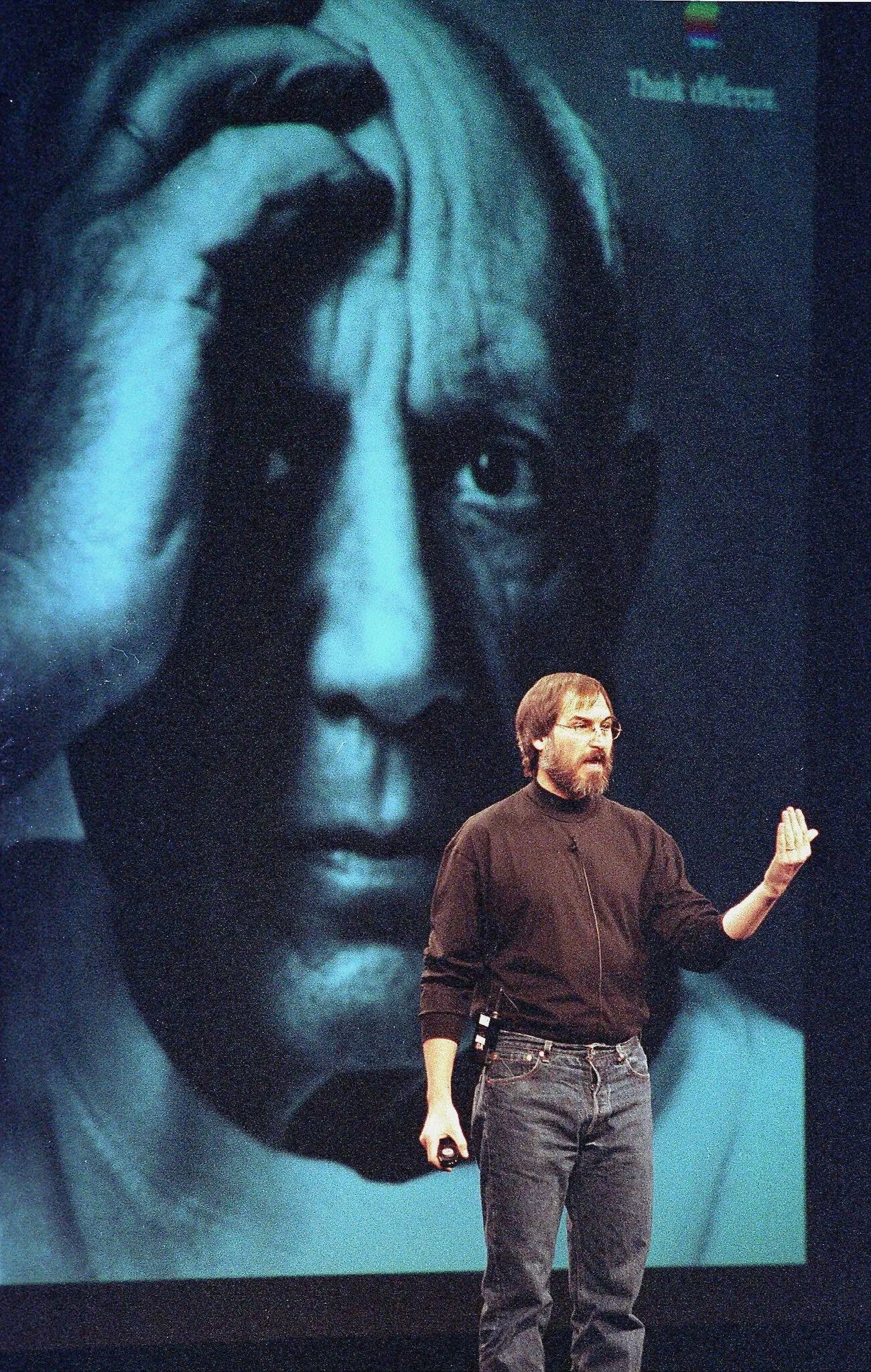

Jobs hired Lee Clow, who had produced the ‘1984’ ad for the Macintosh release, to create a brand image campaign for Apple. Jobs knew that after a decade of stagnation and decline, Apple needed to remind the public what made it so special. Clow created the ‘Think Different’ campaign. The campaign featured an advert with Oscar-winner Richard Dreyfuss reading a speech that began, ‘Here’s to the crazy ones…’ and posters with a black-and-white photo of iconic historical figures such as Einstein, Picasso and Thomas Edison, and the words ‘Think Different’ in the corner beside the Apple logo. Jobs was obsessed with getting what he believed to be the best photos despite some being unavailable. The photo of Gandhi he wanted was owned by Time-Life Pictures but Jobs called the editor-in-chief Norman Pearlstine and convinced him to allow Apple to use it. He also called Eunice Shriver and met with Yoko Ono to persuade them to give him previously unreleased photos of Bobby Kennedy and John Lennon. Jobs would park in the handicapped spaces by the front door of Apple’s office and in response employees made signs saying, ‘Park Different’.

In September 1997, after ten weeks of being an ‘advisor’, Jobs became interim CEO. He took a salary of only $1 a year and refused Woolard’s offer of 4 million shares. Apple had lost $1 billion over the previous year and was just ninety days from insolvency. The company made $45 million in his first financial quarter as interim-CEO, and $309 million in his first year. In 2000, he became Apple’s permanent CEO. In the two and a half years since he became interim CEO, Apple’s share price had gone from $14 to $102, and the shares Jobs had been offered were worth $400 million, whilst Jobs had only earned $2.50. Woolard again offered Jobs shares but he refused and said he’d prefer to have use of a private jet instead to make the increasing amount of travel he had to do more comfortable. Woolard agreed and again offered him the 14 million stock options but Jobs instead demanded 20 million. Woolard was stunned by Jobs’s sudden change of heart and told him that the shareholders had only authorised him to grant 14 million. Jobs was stubborn and a compromise was made where he would receive 10 million shares in January 2000, and another 10 million in 2001.

In 2000, Woolard resigned from the board, exhausted at constantly battling Jobs.

Jony Ive

Jony Ive was born in London in 1967. His father was a silversmith who took him to his workshop to work on a design together once a year as a Christmas present.

He studied industrial design at university, where he first used a Macintosh and felt a ‘connection with the people who were making this product’. When he graduated, he founded a design company called Tangerine which Apple ended up hiring. In 1992, he began working at Apple and in 1996 he was made head of design. When Jobs became interim CEO in September 1997, Jony Ive had been about to quit Apple but Jobs gave a speech declaring that the company needed to focus on making great products rather than trying to maximise profits which convinced him to stay.

When he returned to Apple, Jobs began looking externally for a world-class designer. However, shortly afterwards he met Ive and when realised how talented he was, he stopped looking. Jobs and Ive both believed in aiming for a very specific type of simplicity. Ive explained, ‘Why do we assume that simple is good? Because with physical products, we have to feel we can dominate them. As you bring order to complexity, you find a way to make the product defer to you. Simplicity isn’t just a visual style. It’s not just minimalism or the absence of clutter. It involves digging through the depth of the complexity. To be truly simple, you have to go really deep. For example, to have no screws on something, you can end up having a product that is so convoluted and so complex. The better way is to go deeper with the simplicity, to understand everything about it and how it’s manufactured. You have to deeply understand the essence of a product in order to be able to get rid of the parts that are not essential.’ Ive described how this worked in practice, ‘We wanted to get rid of anything other than what was absolutely essential. To do so required total collaboration between the designers, the product developers, the engineers, and the manufacturing team. We kept going back to the beginning, again and again. Do we need that part? Can we get it to perform the function of the other four parts?’ Together, Jobs and Ive designed all of the revolutionary products released during Jobs’s second stint at Apple.

Ive became one of the most important people in Jobs’s life. Jobs said of him, ‘The difference that Jony has made, not only at Apple but in the world, is huge. He is a wickedly intelligent person in all ways. He understands business concepts, marketing concepts. He picks stuff up just like that, click. He understands what we do at our core better than anyone. If I had a spiritual partner at Apple, it’s Jony. Jony and I think up most of the products together and then pull others in and say, “Hey, what do you think about this?” He gets the big picture as well as the most infinitesimal details about each product and he understands that Apple is a product company. He’s not just a designer. That’s why he works directly for me. He has more operational power than anyone else at Apple except me. There’s no one who can tell him what to do, or to butt out. That’s the way I set it up.’ Jobs’s wife Laurene said, ‘Steve is never intentionally wounding to him. Most people in Steve’s life are replaceable but not Jony.’

Like others before him, Ive was frustrated that Jobs would sometimes take credit for his ideas. ‘He will go through a process of looking at my ideas and say, “That’s no good. That’s not very good. I like that one” and later I will be sitting in the audience and he will be talking about it as if it was his idea.’

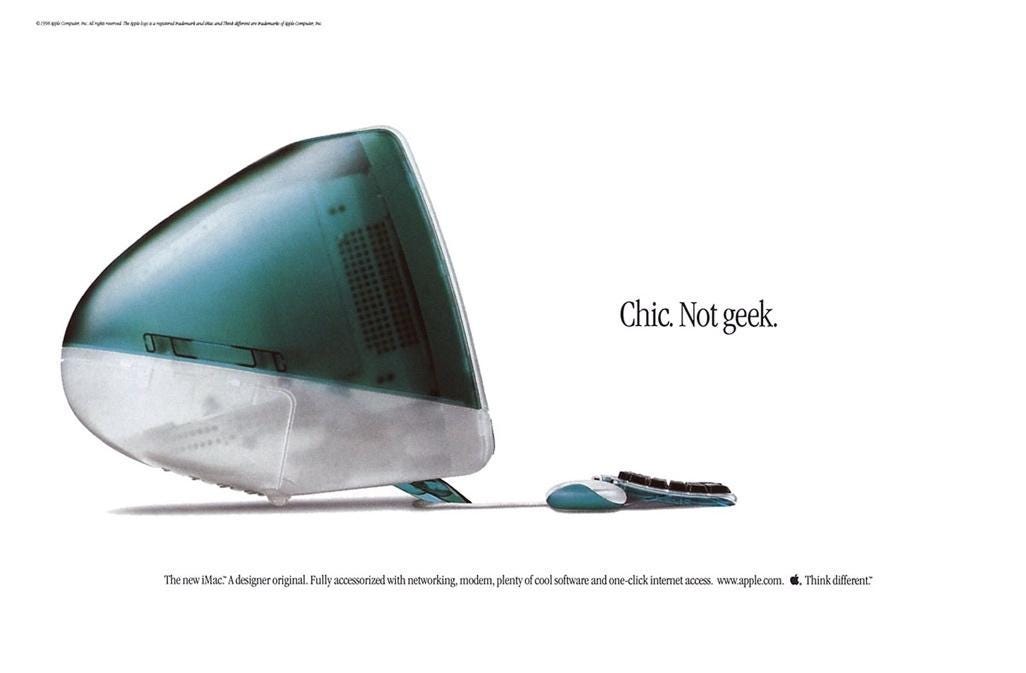

The iMac

In 1998, Apple released one of the four products Jobs had announced they were focusing on after reviewing the product range – a consumer desktop called the iMac. The ‘i’ in the name stood for internet.

The iMac had a translucent turquoise plastic case which showed the components inside. Lee Clow created magazine ads for the iMac. When Jobs saw them, he called Clow and angrily complained that the blue in the adverts was a different shade from the case. Clow insisted that they were exactly the same but Jobs became even angrier and threatened to find a different advertising agency if the advert weren’t changed. When Clow showed him the case and the advert side by side, Jobs finally relented. Years later the following story was posted online by someone who worked at a supermarket near Jobs’s house at the time of the iMac release: ‘I was shagging carts one afternoon when I saw this silver Mercedes parked in a handicapped spot. Steve Jobs was inside screaming at his car phone. “Not. Fucking. Blue. Enough!!!”’

Jobs gave a dramatic presentation of the iMac just like he’d done for the Macintosh fourteen years earlier. He unveiled the computer from under a cloth, clicked on the mouse, and all the computer’s functions flashed across the screen. Then the word ‘hello’ was displayed on the screen in the same handwritten font that had been used at the 1984 Mac launch, with the word ‘again’ in brackets beneath it.

The iMac became Apple’s fastest ever selling product at the time, selling 278,000 units in the first six weeks, and 800,000 in the first year.

Apple Stores

Jobs believed in controlling every aspect of the customer experience and he realised Apple didn’t control the customer’s shopping experience, so in 2000 he hired Ron Johnson to create Apple Stores. The board was sceptical but they agreed to trial four stores. Jobs wanted to impute Apple’s values in the shops. They would be large units in popular shopping malls to emphasise that Apple was a large company aiming for the mass-market, they would be sleek and minimalist like the products themselves and they would have space for customers to play with the products to reflect the creativity they enabled. Jobs and Johnson rented a warehouse and started building a prototype Apple Store. Every Wednesday morning for six months they debated different ideas and reworked different proposals. When the board saw the prototype, they unanimously agreed to build the actual stores. Jobs incorporated the ‘floating’ staircase he had commissioned for the headquarters at NeXT and the blue-grey Pietra Serena sandstone flagstones he had seen on his trip Florence with Tina Redse after he was fired from Apple. During one design meeting, Jobs spent half an hour deciding exactly which shade of grey the toilet signs should be. The first stores opened in 2001. They were predicted to be a failure but in 2004, Apple became the first retail company to generate $1 billion in revenue from their stores. In 2010, they grossed almost $10 billion.

The Digital Hub

Jobs had a vision for computers as a hub which could be used to coordinate lots of different devices. This approach had two advantages. First, a computer hub allowed the linked products to be made simpler because a lot of their complicated functions could be outsourced to the computer. Second, creating useful software for the computer hub would make the linked devices more valuable. For example, video editing software made a video camera much more valuable because it allowed people to make professional looking videos rather than just accumulate lots of raw uncut footage. The digital hub vision vindicated Jobs’s commitment to end-to-end integration because hardware and software which was designed to work together would perform better and have fewer interface problems and this gave Apple a massive competitive advantage because they were the only major company which specialised in both hardware and software.

iTunes and the iPod

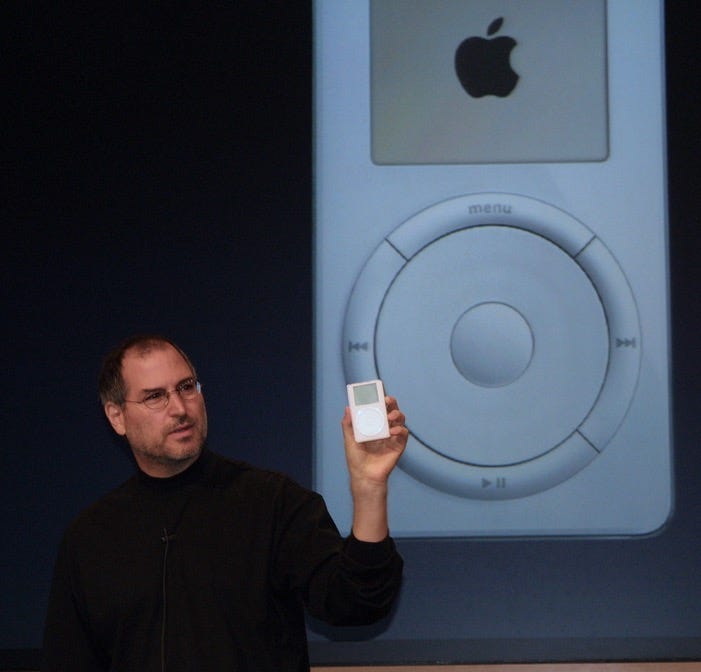

As part of the digital hub vision, Jobs decided to create a portable music player and a music application. People were uploading music onto their computers from CDs and downloading it from the internet and he realised that allowing people to manage their music using a computer and an MP3 player was a huge opportunity. Other companies had already recognised this and he was worried that Apple had fallen behind. However, the music apps and MP3 players at the time were overly complicated and he knew Apple could build better ones.

Three former Apple software engineers, Bill Kincaid, Jeff Robbin, and Dave Heller had created a programme called SoundJam which allowed users of the Rio MP3 player to link it to an iMac. Apple acquired SoundJam and Kincaid, Robbin and Heller started working to develop SoundJam into the simple music application Jobs wanted, which ultimately became iTunes. Jobs considered Jeff Robbin so important to Apple that he refused to allow a reporter to meet him unless he promised not to print his last name.

iTunes was released in January 2001.

Whilst developing iTunes, Apple began working on a portable music player. They found a small LCD screen and a suitable rechargeable battery but they couldn’t find a disk drive which was both compact enough for a small device and had enough memory to hold hundreds of songs. Apple’s Senior Vice President of Hardware Engineering, Jon Rubinstein, went on a trip to meet Apple’s suppliers in Japan, where a Toshiba engineer mentioned that they’d created a 1.8-inch drive which held 5GB but weren’t sure what it could be used for. Rubinstein kept a poker face and then rushed away to tell Jobs. Apple bought the exclusive rights to the disk drive and Rubinstein hired Tony Fadell lead the development team.

Jobs realised other MP3 players were too complicated, and he wanted Apple’s to be simple and intuitive. The team developed a track wheel which made it much quicker to choose options from a list than having to repeatedly press a button. For the user interface, Jobs insisted that any song or function should be available in three clicks and the pathway should be obvious. To keep the device simple, Jobs wanted as many functions as possible to be outsourced to the computer. For example, playlists could only be made on iTunes.

Jony Ive wanted the iPod’s design to set it apart. He explained, ‘Most small consumer products have this disposable feel to them. There is no cultural gravity to them. The thing I’m proudest of about the iPod is that there is something about it that makes it feel significant, not disposable.’ He suggested that the iPod, its headphones and its charger should all be pure white. Lee Clow incorporated the idea into the advertising campaign he created. He created billboards and posters with silhouettes of people dancing with their iPods with the tagline ‘1,000 songs in your pocket.’ The pure white highlighted the iPod against the colourful backgrounds.

Apple released the iPod with another of Jobs’s iconic presentations in October 2001. In 2005, twenty million iPods were sold and by 2007, iPod sales accounted for half of Apple’s revenues.

The iPod and iTunes were key parts of Apple’s digital hub strategy. iTunes drove sales of the iPod which in turn drove sales of the iMac.

The iTunes Store